GRAN FINAL: Reflexiones de un PM en un mal día / GRAND FINALE: The deliberations of a PM on a bad day

Versión en Español / English version below“Enfrentarse, siempre enfrentarse, es el modo de resolver el problema. ¡Enfrentarse a él!”. – Joseph Conrad

Si han estado siguiendo esta serie de artículos (véanse secciones anteriores I, II, III), es natural que a estas alturas del partido estén algo frustrados. Y es que la mezcla de problemas técnicos y humanos detrás de la epidemia de fallas en proyectos es apabullante: ¡En que “broncón” nos hemos metido!. Pero no estamos aquí para llorar, así que vamos valientes con el contrataque. Divide y vencerás: aprovechemos más bien que tenemos agrupados a los “enemigos” en dos subgrupos para entrarle al tema. Primero la parte de los procesos – la menos interesante a mi parecer – y luego hablemos de las personas y nuestra (valga la redundancia) absurda capacidad para el absurdo, para equivocarnos y para engañarnos. Veamos:

Cómo mejorar los procesos y la organización

Acerca de este tema (debilidades organizacionales y procesales), mi opinión es que debemos implementar un enfoque más estructurado, que nos ayude a “ordenar la casa”: salgamos del “cajón PMI”. Afortunadamente, no tenemos porque “re-inventar la rueda”: la metodología PRINCE2 del Gobierno Británico tiene precisamente esa perspectiva (no en vano se refiere a “Projects in Controlled Environments“). Rescato de ella los siguientes puntos a ser emulados en este nuestro hemisferio occidental:

- El PM como Manager: Primero que todo, la estructura organizacional debe reflejar el hecho de que el Gerente de Proyecto, léase el PM es… ¡un Gerente y punto! Eso significa que esta persona tiene las potestades y habilidades para gestionar el proyecto, pero nada más. No es el PM la persona que debe generar el caso de negocio, el project charter o quien autoriza proyectos o fases. La metodología PRINCE2 es clara y estipula tres niveles: Nivel Directivo, compuesto por un “Board” que dirige el proyecto, nivel de Gerencia (Management), al cual pertenece el PM, y el nivel de Delivery el cuál ejecuta las tareas como tales. Ese Board es quien toma las decisiones ejecutivas – es “su” proyecto, el “accountability” reside últimamente sobre el Board. Agrego de mi parte que el PM debe tener voz pero no voto en ese organismo.

- El “Project Executive”: es equivalente al “Project Sponsor” en terminología PMI, pero que ostenta un grado de involucramiento y proactividad mucho mayor. El Project Executive es algo así como un coach y guía activo para el PM y toma decisiones ejecutivas para el proyecto, pero desde un punto de vista de NEGOCIO. Podría decirse que el “Project Executive” es el “Project Sponsor” que todo PM sueña con tener: alguien que, siempre desde un punto de vista estratégico, pero que no teme “ensuciarse las manos” por y para el proyecto .

- Rescatar la importancia del “Business Case”. Los proyectos se hacen por una razón. Sus entregables y objetivos deben ser deseables, valiosos y alcanzables. Todo esto debe de estipularse claramente por escrito en el Caso de Negocio, y este documento debe ser el verdadero punto de referencia para las decisiones directivas sobre el proyecto (eg, aprobación, VoBo para la siguiente fase, Cierre, Cancelación prematura, etc.). Debe consultarse por el Board y el PM a lo largo de todo el proyecto con énfasis al inicio y al cierre del mismo.

- Definición de rangos de tolerancia para el presupuesto, tiempo y alcance, entre otros: el PM toma las decisiones en tanto no se salga de esos rangos. En cuanto la tendencia sea claramente hacia salirse del rango o bien se salga del mismo, debe escalar inmediatamente al Project Executive para recibir instrucciones ad-hoc sobre el caso en particular. Cuando las cosas se salen de control entonces el Board debe “tomar el timón”.

- Utilización de los 7 principios mencionados en PRINCE2: justificación continua / revisión continua del caso de negocio, gerenciamiento por fases, gestión por excepciones, roles y responsabilidades definidos, enfoque en los beneficios, entre otros.

- Cierre del proyecto: esta decisión NO debe ser competencia del PM. En realidad, esta es una responsabilidad exclusivamente del “Board”. En pocas palabras, el proyecto no fue una ocurrencia o idea del PM, tampoco debe ser el PM quien autorize y comunique su cierre. El PM es un delegado, un ejecutor que lleva a cabo el proyecto, pero el proyecto como tal y su enfoque dentro del negocio (la consumación de los beneficios) es un asunto del Board y de nadie más. Valga mencionar que esto aplica también para los CAMBIOS al proyecto, sean estos de alcance, tiempo o fondos.

- Implementar un Reporte de Cierre del Proyecto: en mi opinión personal, si este reporte es implementado y ejecutado de manera correcta sería entonces mucho más valioso para la organización que las (casi, casi siempre) difuntas, marchitas, inertes y olvidadas “lecciones aprendidas”. En mi experiencia, casi nunca se generan las famosas “lessons learned” y cuando sí se recolectan terminan convertidas en listados olvidados en un rincón de “SharePoint” o en un archivo de Excel. Es por eso que sugiero enfáticamente que se implemente la generación de un Reporte de Cierre del Proyecto, lo más corto y sencillo posible, en donde se indique claramente el alcance original vs el final, costo original vs final, duración original vs final, recursos originalmente programados vs utilizados y los “gaps” correspondientes así como (muy brevemente) las razones detrás de esos “deltas” o diferencias. Además, este reporte debe tener “tags” o etiquetas que permitan alimentar una base de datos (eg, tamaño del proyecto por unidad de ejecución – número de servidores, número de agentes, número de licencias, número de metros cuadrados, etc. etc.. tipo de proyecto, etc.) de forma tal que esta información SI sea accesible y de fácil consulta a la hora de lanzar un nuevo proyecto. La base de datos se convierte entonces en una verdadera referencia , un registro histórico que con hechos y evidencia demuestra cuanto es lo que verderamente tardamos en promedio en un proyecto de X cantidad de servidores, Y cantidad de líneas de código ó Z cantidad de metros cuadrados, ¿Se imaginan ustedes el valor que tiene esta información para el Board y para los que venden los proyectos? ¿Y qué tal como fuente de datos para sistemas expertos / inteligencia artificial? (véase punto más abajo)

- Finalmente, la gobernanza organizacional como tal debe mejorar. Resumiendo, la gobernanza organizacional se encarga de definir los objetivos así como las políticas (reglas) & restricciones a respetar a la hora de ir por esos objetivos. En otras palabras, la gobernanza organizacional es asunto del más alto nivel (VPs, C-Suite, Exec Board) y nada más. Es a este nivel que se crean las condiciones, diríamos el “medio ambiente” para que la Gerencia pueda operar exitosamente. En mi opinión, el PMI en el “Practice Guide for the Governance of Portfolios, Programs, and Projects” comete el error de mezclar aspectos de gerencia con aspectos de gobernanza, y por lo tanto le asigna responsabilidades de gobernanza a niveles medios y bajos de la organización. De mi parte, quedo con la tarea de estudiar el estándar ISO/IEC 38500:2015 “Governance of IT for the organization” y el estándar ISO/AWI 37000 “Governance of organizations”: debe haber una manera de “cocinar” correctamente la mezcla de gobernanza organizacional con la de gobernanza de los proyectos (quizás esto implique además el estudio del estándar ISO 21500 “Guidance on Project Management” y aún otros documentos). Creo que solo este punto amerita, en el futuro, un nuevo post…

Cómo mejorar la gestión y las decisiones tomadas por las personas

¡Ah, el ser humano! He aquí el verdadero quid de la cuestión: si tan solo fuéramos todo lo lógicos, racionales e informados que se supone que somos. Si tan solo el personal de las organizaciones y particularmente los tomadores de decisiones tomarán sentencias en función de criterios objetivos y evidencia… pero no. Lamentablemente, los seres humanos somos cualquier cosa menos eso, estamos llenos de sesgos, subjetividades y heurísticos. Errare humanum est… Siendo así, tratemos de que el sistema compense un poco nuestras faltas personales, propongo los siguientes puntos:

- Metodología de las votaciones: Las votaciones de los Boards deben ser públicas… pero no “seriales” ni en tiempo real. A lo que voy es que para evitar el sesgo mental de “mentalidad de manada”, las tomas de decisiones de organismos colegiados (Boards y similares) deben ser ciertamente públicas (cada miembro debe ser responsable de su voto ante los demás y ante la organización) PERO eso no significa que deba votarse uno después del otro y a sabiendas de cuál fue el voto de mi antecesor. El ejercicio del voto de aprobación o rechazo de un proyecto, fase, cambio, cancelación, presupuesto etc. debe ser simultáneo para todos los miembros y debe comunicarse el resultado minutos después por una figura de “secretario” o similar. De esta forma evitamos el comportamiento “de manada”.

- Veto: Aunado a lo anterior, debe existir la figura del VETO. No tengo aún claro si esta figura debería ser potestad de todos en el Board o solo de un grupo aún más selecto, pero alguien debe de poder poner al menos en pausa una idea o proyecto. La figura del Project Executive arriba mencionada es tentadora para esta atribución tan especial.

- Otras herramientas para las decisiones: Existen otras metodologías que podemos implementar para mejorar la calidad de las decisiones. Algunas de ellas son:

- “Murder Board”: este interesantísimo ejercicio mental nos propone explícitamente el ponernos en el papel del fiscal y tratar de “asesinar” a las iniciativas y proyectos. Esto es un valioso punto de vista porque en caso que todos los proyectos tengan un ROI positivo (lo cual es esperable, nadie va a proponer un proyecto que no tenga ese carácter financiero) entonces todo es apetecible. Y entonces los seres humanos caemos en la gula… no podemos decir que no: ¿cómo vamos a justificar el decir que no si tal proyecto va a redituar X cantidad de dólares y ese otro Y cantidad? Por supuesto, lo que no estamos viendo es que esos dos proyectos van a sobrecargar la capacidad de la organización y al final atrasaremos a toda el portafolio, causaran multas, problemas de calidad, fricciones con los clientes, “quemarán” al personal. etc.

- Comparación 1-a-1: se trata de poner a los proyectos a competir uno-contra-uno. Como en la Copa del Mundo, los proyectos compiten unos con otros hasta descubrir quién es el campeón, sub-campeón y en general producir un ranking.

- Mercado Virtual: excelente metodología de trabajo que nos induce – literalmente – a(y me disculpan el coloquialismo) “ap poner la plata donde ponemos la boca”. A cada representante del Board (cada Director, VP o lo que fuere) se le asigna un monto virtual de dinero y esa persona debe entonces decidir que monto va a asignarle a cada uno de los proyectos / propuestas en el pipeline. Lo que sucede entonces es que la mente pasa de modo “se vale todo” a modalidad “recursos limitados” y se dispara un proceso analítico que genera una priorización automática.

- Implementación de la metodología “Six Thinking Hats”: este método de pensamiento creado por Edward de Bono nos propone ponernos deliberadamente diferentes “sombreros”, diferentes “modos” o roles de análisis: Procesos, Hechos, Sentimientos, Creatividad, Beneficios y Precauciones. Se asumen entonces diferentes perspectivas que permiten analizar el proyecto/caso/situación desde todos los ángulos.

- Cuéntame… pero no un cuento: Para atacar sesgos mentales/cognitivos como el Anclaje y la Disponibilidad, no veo otra solución mas que, como diría Steven Pinker, contar. Es decir, dejémonos de tonterías e intuiciones y vamos a los DATOS: “gimme facts baby, facts!“. Es aquí donde la implementación y uso del reporte de cierre de proyectos y una base de datos “for dummies”, de uso fácil e intuitivo es crucial. Necesitamos SABER cuánto es lo que tarda/cuesta/demanda-de-personal/equipo en la vida real un proyecto de este tipo y este tamaño. Los datos están ahí pero no en una forma digerible: no es información. Sugiero que nos olvidemos (al menos de momento) de los cuentos y prosas de las lecciones aprendidas (las cuales, como mencioné, casi siempre solo “apilan polvo”) y vayamos directo a los números. De esta forma, si el caso de negocio o el Charter del proyecto indica una duración que supone la mitad del promedio del tipo X de proyecto… necesitaremos una justificación al respecto: no es eso lo que dice la experiencia: ¿Está usted tratando de timarnos?

- El ROI: Y hablando de hechos, evidencias, datos y números, un elemento adicional a “rescatar del olvido” es el ROI. Y digo rescatarlo del olvido no porque no se presente junto con el “Business Case”… sino porque (muchas veces) inmediatamente despúes se olvida. Vamos a ver: cuando se está manejando un portafolio dinámico y grande de proyectos, en muchas ocasiones se exige la presentación del ROI como un requisito para aprobar el proyecto, PERO:

- No se comparan los ROIs de diferentes proyectos, ni se realiza un ranking.

- No se revisa/actualiza el ROI conforme el proyecto se desarrolla (conforme cambia la duración, alcance o costo)

- Y – peccata mortalia (pecado mortal) – no se revisa AL FINAL del proyecto ni tampoco cuando el producto(s)/entregables se han implementado: en otras palabras, no sabemos si financieramente el proyecto hizo sentido o si el ROI fue nada más una linda postal presentada para cumplir con un requisito.

- Rapidez: Un criterio & parámetro adicional que puede ser agregado a los proyectos es el “speed-to-market”: en el mundo actual, la velocidad de implementación es cada vez más importante. De esta manera, proyectos “low-hanging-fruit”/”early winners” pueden tener su nicho en el portafolio/pipeline.

- No va más: Debemos “prohibir” el así llamado “one-time-estimate” de una vez y por todas. Necesitamos como mínimo utilizar el enfoque de mejor escenario – más probable – peor escenario (y la fórmula de ponderación asociada), pero lo idóneo es utilizar probabilidad / estadística y registros históricos.

- “Watson-time”: Además, creo que ha llegado la hora de darle espacio a la Inteligencia Artificial. Esto aún es incipiente pero la AI tiene la ventaja de que es un enfoque fáctico: utiliza datos y proyecciones matemáticas, no intuiciones, rezos y esperanzas. Una correcta implementación de esta herramienta puede “iluminarnos” no solo acerca de las verdaderas fechas esperadas para finalizar tal o cual fase, entregable o proyecto (proyecciones estadísticas), sino que también puede proveer poderosos insumos a la hora de evaluar la alineación de los proyectos y sus cambios con la estrategia organizacional (véase el artículo II de esta serie, en donde se menciona el top 7 de causales de fallos de los proyectos). Veo incluso una oportunidad para mejorar la comunicación organizacional (intra e inter proyecto) por medio de la AI.

Y nos vamos: cierre

No pretendo tener todas las respuestas. Tampoco estoy sugiriendo que el conjunto de propuestas e ideas arriba enlistadas sean una solución total, una “bala de plata” que acabe con este problema. Sin embargo, la mezcla adecuada de estos factores puede servir – cuando menos – como un poderoso paliativo para esta epidemia de proyectos enfermos y fallidos que nos asolan cual zombis de película de terror.

Tengo aún otras ideas en mente (entre ellas, la integración del Riesgo en el análisis), pero primero quisiera escucharles. No dejen de enviar sus comentarios o bien escríbanme a [email protected] . Einstein dijo una vez “No esperes resultados diferentes si sigues haciendo lo mismo” – pensemos entonces “fuera de la caja” y ataquemos de frente este engorroso asunto. Debemos abandonar de una vez y por todas esa visión fantástica e imaginaria en la que el PM es algo más que un simple Gerente y se le adosan funciones directivas y estratégicas, una especia de superhéroe sin capa: difiero completamente de esta idea. Hay un nivel organizacional adecuado para cada nivel de decisión. Así, el PM tiene un rol táctico y una voz sobre las decisiones globales del proyecto, más ciertamente su rol no es estratégico.

Y bueno, supongo que es suficiente: ¡He dicho! Ahora, les escucho…

ENGLISH VERSION

“Facing it, always facing it, that´s the way to get through. Face it.” – Joseph Conrad

If you have been following this series (see prior posts I, II, III), it´s totally understandable that at this time you feel somewhat frustrated. It´s just that the mix of technical and human problems is overwhelming: what a monster! But we are not here to play the cry-baby, lets proceed with a brave counterattack. So, divide and conquer: let´s seize the fact that we got the issues divided into tech and human categories. Let´s start with the process/organizational aspects and then let´s jump to the (to my taste) more interesting human side of the conundrum. Check this out:

How to improve the processes and the organization

On org and process weaknesses, my opinion is that we should implement a more structured approach that attacks the “house divided against itself” syndrome. My take: let´s jump outside the “PMI box”. Luckily, we don´t need to re-invent the wheel, UK´s PRINCE2 methodology enforces that holistic, org perspective (after all, it´s name is “Projects in Controlled Environments“). I want to highlight the following points which should be emulated in this our Western Hemisphere:

- The PM as PM: First and foremost, the org structure needs to reflect the fact that the Project Manager is… just a manager! That means that this person has the skills and authority to manage the project but that´s about it. It is not the PM the one supposed to create the business case, the project charter or the one approving projects, phases or changes. The PRINCE2 methodology is clear on this, listing three org levels to deal with three levels of concerns: Directive Level, composed by a “Board” that actually leads and steers the project, then a Management level that is concerned with tactical stuff (the PM is part of it) and a Delivery level that is executing tasks and creating deliverables. It is the board the one taking executive decisions: at the end, it is THEIR project, since accountability rests on the Board. From my end, let me add that the PM should have a voice but not a vote in the Board.

- Project Executives: Summed to the prior point, we desperately need to implement the role of the “Project Executive”, a PRINCE2 equivalent to the “Project Sponsor” (as per PMI framework), but with a level of involvement and proactivity much farther ahead. The Project Executive is sort of a coach and active guide for the PM and actually takes executive decions for the project, but this person has a BUSINESS vantage point. We could say that the the Project Executive is the Sponsor that all PMs dream for: someone who, with a strategic and business perspective, is always willing to take decisions and actually “get the hands dirty” in order to make the project succesfull.

- The “Business Case”: Projects are done for a reason. Their deliverables must be desirable, valuable and achievable. All this – and more – must be clearly stated in the Business Case. This doc is the real anchor and “map” serving as a reference for exec decisions (eg, Phase approval, Closure, Cancellation, etc.). It must be regularly checked by the Board, the Exec and the PM, especially during project Launch and Closure.

- Tolerances: one-point definitions for budget, time, QA-aspects and others are a bad idea. The PM should have tolerances in order to properly manage the project. When there is a trend pointing toward upcoming out-of-range or factual out-of-range/tolerance, the PM must immediately escalate to the Executve and receive ad-hoc instructions. Possibly, the Board could be involved in order to steer toward more “calmed seas”.

- Usage of the 7 PRINCE2 principles:

- Continued business justification, the project should be beneficial, and stay so.

- Learn from experience, we are not supposed to reinvent the wheel.

- Define roles and responsibilities,each person should know what others expect from them, and what they can expect from others.

- Manage by stages, project should be broken down into stages, and planned/executed/controlled accordingly.

- Manage by exception, there should be a well-formed system for delegation and escalation.

- Focus on products, rather than on activities.

- Tailor to suit the project environment.

- Project Closure is NOT a decision/competence of the PM: this is something to be defined by the Board. In other words, the project was not the PM´s idea, so… why should him/her determine its ending? The PM is a delegate, responsible for the day to day management of the project in behalf of the Project Board, but the project and its business perspective (such as benefits) is beyond his/her duties. Let me add that this applies to Changes as well, regardless those being related to scope, time or budget.

- Implement a Project Closure Report: in my opinion and as long as it is implemented correctly, this report is far much valuable to the org than the (almost always) passed-away, dead, withered, droopy lessons learned. As a matter of fact, lessons learned are seen as of a bureaucratic hurdle to be avoided or dealt with on a “get-rid-of-it” basis. That´s why they tend to be forgotten in “dusty” lists in SharePoint or Excel. That´s why I strongly advise to collect DATA: original scope vs actual final scope, original budget vs actual final spending, original duration vs actual final duration, planned ROI vs actual ROI (among other) and (really briefly) the rationale behind the deltas/differences. And perhaps even more importantly, this data needs to be fed into a DB under the right tags and search criteria, in order to make it truly available for next project (and possibly, even AI-powered advisers). The project associated to the data should be characterized in the adequate terms (eg, number of servers, number of agents, number of licenses, number of square meters/feet, etc.) In this way data becomes info. The DB is a handy tool, a historical repository of truth that with facts and evidence states the true cost, duration, ROI, etc. of X type of project. Can you imagine the value of this info for the C-suite, Sales, Consulting and the Board?

- Last but not least, organizational governance needs to improve – and a lot! Briefly, org governance deals with the definition of the org objectives as well as the policies, rules and restrictions to respect when operating toward those goals. In other words, org governance is a topic for the highest org levels (VPs, C-Suite, Exec Board) and no one else. It is at this level that the conditions, that a successful environment is created for Management to operate (in turn) successfully as well. In my humble opinion, the PMI mixes management and governance aspects within the “Practice Guide for the Governance of Portfolios, Programs, and Projects” doc. I will put into my to-do list the study of the ISO/IEC 38500:2015 “Governance of IT for the organization” and the ISO/AWI 37000 “Governance of organizations” standards: there must be a way to correctly “cook” the blend between organizational and project governance (perhaps this also implies a deep-dive into the ISO 21500 “Guidance on Project Management” title and even other documents). I guess just this point accounts for a new post in the future: stay tuned!

How to improve the human factor (especially, the decision process)

Gosh, the human being! This is THE issue… if we just could be as logic, rational and informed as we are supposed to be. If org staff – and decision takers in particular – could make their calls as a function of solid criteria, facts and evidence, but… no. Sadly, we human beings are totally prompt to bias, subjectivity and heuristics. Errare humanum est… Being that the case, let´s try to make the system a little less easy to hack by our humanity, I suggest the following practices:

- Board votings should be public… but indeed not “serial” nor in 100% real-time. What I mean is that in order to avoid the “herd mentality” bias, decisions from boards and the like should be kept public for the sake of accountability, but that does NOT means that each member should vote one after the other, getting to know each one´s vote. The voting exercise should be simultaneous for all members and the result should be communicated a couple minutes later through a secretary-like figure. In this way, we avoid the herd behavior.

- Plus, the VETO figure should be available. I am not sure if this capability should be available to all the Board members or just to a select group, but someone must have the power to pause an idea or project. The Project Executive figure is a nice candidate for this (more on this figure below).

- There are other methodologies we can use to improve the quality of decisions. Some of them are:

- “Murder Board”: this is a really interesting mental exercise, which actually puts us in the prosecutor role and we try to “kill” initiatives and projects. This is valuable because (normally) all projects have a positive ROI (else, why should we do them – no one is going to suggest a project with a negative financial outcome), thus, everything looks just “yummy”… and orgs get greedy. I mean, how can we say no to project “A” if it´s going to generate actual revenue? Its good for us! And what about project B? And C? And X? Of course this line of (no) thought leads into “stack overflow”, overloading the pipeline, delaying the entire portfolio, frictions with customers, fines, staff “burnout” etc.

- Paired comparison: this one is about putting the projects to compete F2F. Like the World Cup, the projects “eliminate” against each other until we have a champ, a runner-up and a general ranking. Great for priotitization!

- Virtual Market: superb methodology that literally makes us put the money where we put the words. Each Board representative (Director, VP, you name it) is assigned an amount of “virtual money” and then they got to assign funds to the projects according to their best criteria. What happens is that the decision takers shift from a “anything goes” to an analytical mindset.

- “Six Thinking Hats” methodology: this method, created by Edward de Bono, pushes for the person to play different thinker roles, including the Process, Facts, Feelings, Creativity, Benefits and Caution ones. As such, we got a structured approach to analyse the project/topic through a variety of angles.

- 1…2…3… lets count: In order to attach cognitive biases such as the Anchoring and Availability ones, I don´t see any other option but actually (as Steven Pinker says) counting. I mean, let´s cut to the chase: I want to see DATA. No more poppycock: “gimme facts baby, facts!“. It is here where the implementation and usage of the Project Closure Report and a “for dummies” DB is crucial. We need to KNOW how much/how long/how much staff & equipment does this type of project actually entails. In my experience, data is there but not as info: its nebulous. I suggest for us to forget (at least for the time being) about the dusty prose in lessons learned and go direct to numbers. In this way, if the Business Case or Charter states a duration of, say, half the average for this kind of project, there will be an immediate warning sign – a justification is needed. Is someone lying?

- ROI: And speaking of facts, evidence, data and numbres, an additional element to rescue from oblivion is the ROI indicator. And I am saying “rescue from oblivion” not because it is not calculated, but because it is done once (during the business case or charter creation) and then sent to another pile of dusty docs. It is created as a requirement to present the project but that´s about it. Hence:

- There is no comparison of the ROIs of different projects, needless to mention the absence of a ranking.

- The ROI is not updated as per the unfolding of the project, not to mention when the scope/time/budget changes.

- And – peccata mortalia (mortal sin) – it is not validated at the END of the project nor when the actual product/deliverable is implemented. As such, we don´t know if the project was actually a success from the business/financial standpoint. Nonsense…

- The Fast and the Furious: Another criterion / parameter to add to the analysis is “speed-to-market”: nowadays, the actual velocity of the project delivery or implementation is key. As such, “low-hanging-fruit”/”early winners” projects will have their niche in the portfolio/pipeline.

- No more: We should ban once and for all the so-called “one-time-estimate”. We need at least to use the best-case-scenario / most-probable / worst-case scenario formula, and ideally we should jump into statistics derived from solid data: history, facts!

- “Watson-time” – let AI come: Finally, I think it is time to give a space in the stage to Artificial Intelligence (AI). This is still somewhat crude but we need to acknowledge that AI has the superb advantage of using a factual, objective standpoint all the time: data, trends, math instead of gut feelings, hopes and prayers. A correct implementation of this tool could certainly enlighten us not just about the realistic dates for finishing the phase or project but also provide valuable insight as of the alignment of the projects vs org strategy (see section II of this series of articles for the 7 main reasons behind project failure) and the reasons behind gaps and pitfalls. Furthermore, AI can also improve communication, both intra & inter projects and with the org.

Closure remarks

Let me say that I don´t pretend to have all the answers. Neither Im suggesting that the above list of ideas should be taken as a “silver bullet” that will solve this problem like an aspirin takes over a headache. Still, the adequate blend of those (plus others to be identified as per project/org/analyst) can really help to improve the health of projects and portfolios that currently pursue PMs as zombies in a bad movie.

I have even more ideas in mind (eg, the integration of Risk within the analysis, Problem Solving tools, etc.), but I would really like to hear from you first. Please don´t hesitate to send your comments here or write to [email protected] . Einstein said that “the definition of insanity is doing something over and over again and expecting different results” – lets think “outside the box” and tackle this monster directly. We need to abandon once and for all the false vision of a PM with “superpowers”, a magical mix of operational, tactical and strategical skills: kind of an org superhero. There should be an org level for each level of responsibility.

I guess enough is enough. Now, let me hear you guys… cheers!

“Management is doing things right; leadership is doing the right things.” – Peter Drucker

Material Adicional:

Nota/Photo Credit: Photo by Nikita Kachanovsky on Unsplash

Reflexiones de un PM en un mal día (parte III) / The deliberations of a PM on a bad day (part III)

V. ESPAÑOL (English version below)

Proseguimos con este analisis que presenta la causa última ó fundamental detrás del fallo masivo de proyectos en las organizaciones y que además esbozará algunas medidas al respecto. En el post anterior, arguimos qué la verdadera razón detrás de tantos proyectos fallidos en las organizaciones modernas es… la organización moderna. En el fondo, el punto es sencillo: si (casi) todos los proyectos en su organización están fallando, entonces el problema no son los proyectos, sino la organización. Como un tipo que se queja lloroso en un bar de sus últimas 12 novias, el común denominador de tanto intento fallido es el caballero en cuestión, no las damas. Dijimos también que la mejor manera de caracterizar esta epidemia es una gobernanza organizacional deficiente (o inclusive del todo ausente). Veamos este tema de gobernanza corporativa con un poco más de detalle:

Comenzemos con una definición: Wikipedia nos dice que la gobernanza corporativa son los mecanismos, procesos y relaciones por medio de los cuales las corporaciones son controladas y dirigidas. El PMI por su parte define la gobernanza como sigue (voy a dejar la definición en inglés para efectos de purismo semántico): “Governance is the framework, functions and processes that guide activities in project, program and portfolio management. In organizational project management (OPM), governance provides guidance, decision making and oversight for the OPM strategic execution framework.” El RAE indica “Acción y efecto de gobernar o gobernarse”, y a su vez, define gobernar como “dirigir, guiar, mandar con autoridad”, entre otros. Deseo rescatar tres elementos de esta serie de definiciones:

- La gobernanza implica procesos , mecanismos y relaciones

- La gobernanza supone mandato con autoridad

- La gobernanza implica, requiere y demanda la necesidad de tomar decisiones.

Detrás de estos tres elementos críticos de la gobernanza hay un aspecto común: la PERSONA – léase el ser humano. Es la persona la que define los procesos, mecanismos y el que se relaciona, es la persona el que manda y ejerce la autoridad, es la persona la que toma decisiones. Y es aquí donde, citando a Mario Moreno “Cantinflas”: “ahí está el detalle”. Tal y como lo descubrió recientemente la ciencia económica, el ser humano NO es esa entidad lógica, fría, racional, informada y analítica (de hecho los economistas usan el irónico término “econo” para designar a esas entidades imaginarias que solo existen en los libros clásicos de economía). Somos más bien seres impetuosos, sentimentales, ilógicos, prontos a la generalización y al uso de heurísticos (que viva la economía conductual, adalid de este enfoque). En otras palabras: somos pésimos admnistradores, pues nuestra toma de decisiones está afectada por múltiples sesgos y desviaciones. Algunos de las trampas mentales (sesogos cognitivos) que nos afectan son:

- Anclaje: somos increíblemente sensibles a ser sesgados por datos, informaciones y eventos recientes, los cuales “marcan” y afectan nuestra evaluación de los efectos posteriores. Por ejemplo si le pregunto si la distancia entre Chicago y Nueva York es mayor a 1000km y cuál es esa distancia, Ud. probablemente dirá un rango entre 800 y 1200 km. Pero si le pregunto si la distancia es mayor a 500km y cuál es esa distancia… probablmente Usted dirá algo así como 600 o 40okm (la distancia real es de aprox. 1200km). Asimismo, si se echa Usted el café encima al desayunar, puede ser afectado por ese evento todo el día. ¿Irracional? Sí. Pero también es cierto. Imaginemos ahora un escenario en el cual se va a proceder a aprobar presupuestos para iniciar (launch) una serie de proyectos… y el evento inmediatamente anterior en la agenda fue entregar un reconocimiento por un proyecto exitoso (a tiempo, dentro del presupuesto, cumpliendo los requerimientos) a un PM. Adivine Usted cuál va a ser el “tono” general de la sesión de presupuestación… sí, adivinó bien: manos dadivosas.

- Disponibilidad: este sesgo afecta nuestra apreciación de la frecuencia de un evento, en función de la facilidad con que recordamos ejemplos relevantes. Por ejemplo, si hablamos de qué es más frecuente, los homicidios o los sucidios, probablemente nos decantemos por la primera opción puesto que los noticieros nos inundan de fatídicos casos. En el plano organizacional, imaginemos un escenario en donde se está discutiendo la aprobación de una inversión en un proyecto de Inteligencia Artificial (AI) vs invertir en un proyecto de Cloud. Los últimos 2 esfuerzos en la primera tecnología fueron fallidos, mientras que en el área de Cloud fueron exitosos: en este escenario, es muy difícil que se incursione en AI, a pesar de que el proyecto como tal muestre un mejor ROI y sobre todo mejor enfoque estratégico vs la ya “desgastada” área de Cloud computing.

- Sesgo del “status quo”: este sesgo se refiere a nuestra dificultad para romper el “momentum” actual – el curso actual de acción, el estado actual de las cosas pesa mucho, simplemente porque “así se hacen las cosas aquí”. Creo que no hacen falta muchos ejemplos para esta trampa mental.

- Mentalidad de manada: ¡Cuánto pesan en nosotros las opiniones de los demás! Los comercios lo saben y la etiqueta “Bestseller” es un excelente gancho de ventas. ¿Recuerda cuando andabamos de niños en bicicleta y formábamos pandillas? Más de un triste accidente se ha presentado cuando el primer niño cruza una calle y los demás lo siguen sin ver, en un clásico comportamiento de manada. Este tipo de comportamiento tiene su absoluto “mellizo” en la forma en la que las organizaciones reunen al staff para votar sobre el devenir de los proyectos: aprobaciones, presupuesto, cambios, etc. En muchas ocasiones, el primer voto es el del “hippo” (“highest paid person in the organization” – la persona de mayor rango en la reunión/organización) y a partir de ahí la suerte está echada: ese voto determina todo lo demás. Pero independientemente de si el “hippo” es el primero en votar, el voto público tiende a sesgar todo el proceso. Este es evidentemente una pésima metodología para la toma de decisiones y un atentado a la sana gobernanza organizacional.

Súmese a nuestra sesgada humanidad arriba retratada la ausencia de marcos normativos de gobernanza (según vimos en el primer post, solo el 2% de las organizaciones utilizan de manera continua”frameworks” como PRINCE2, véanse los datos exactos en el reporte PMI Pulse of the Profession 2018 (2018)) y tenemos entonces una tremebunda receta para el desastre. En vista de todo lo anterior, debemos hacer algo para mejorar la gobernanza corporativa/organizacional, en procura de una mejora en la gestión de los proyectos (en otras palabras, en procura de una reducción de ese demoledor porcentaje de proyectos falllidos). Si has venido siguiendo esta serie de artículos, creo que ya debes tener una serie de ideas en mente. Voy a compartir las mías… pero en el próximo artículo: quiero contar con toda tu atención y “frescor” mental para lo que sigue.

Me encantaría escuchar sus comentarios en este foro – soy todo oídos. ¡Hasta muy pronto!

“Los hombres no son prisioneros del destino, sino prisioneros de su propia mente.” – Franklin D. Roosevelt

ENGLISH V.

Let´s continue with this analysis that presents the root and core cause behind the massive failure of projects in modern organizations and that will also share some ways to tackle this concern. In the prior post, we discussed that the reason behind epidemic project fails in the orgs are… the orgs themselves. Check the post for details, but at the end the the argument is easy: if (nearly) all projects hurt, then the problem are not the projects but the org. Like a guy sadly and wrongly complaining of his last 12 girlfriends, the common denominator is the guy: the organization itself. The best way to characterize this failure on the “guy´s character” is organizational governance. Let´s get into governance then.

Shall we start with a definition? Wikipedia: “Corporate governance is the mechanisms, processes and relations by which corporations are controlled and directed.”. PMI: “Governance is the framework, functions and processes that guide activities in project, program and portfolio management. In organizational project management (OPM), governance provides guidance, decision making and oversight for the OPM strategic execution framework.” Merriam-Webster: “the way that a city, company, etc., is controlled by the people who run it”. Britannica: “Corporate governance, rules and practices by which companies are governed or run. Corporate governance is important because it refers to the governance of what is arguably the most important institution of the capitalist economy.” I want to highlight three aspects derived from those definitions:

- Governance implies processes, mechanisms and relationships

- Governance supposes ruling with authority

- Governance implies the need of taking decisions.

Subtly and hidden behind those three critical elements a new common denominator hides: the person, the human being. It is the person – the organizational staff, and particularly the Board and C-Suite, the leaders – the ones that define processes, mechanisms and relationshops, it is the person the one that holds authority and it is the person the one taking decisions. But the devil is in the detail: as the Economics Science recently discovered, the human being is NOT that logical, cold, rational, fully informed and analyticial creature pictured in classic economy textbooks (as a matter of fact, modern economists have coined the term “econs” in order to differentiate those “Vulcanians” from normal human beings). Contrarily, we are impetuous, sentimental, illogical, heuristical and bias-prompt creatures (we can talk more on this from the behavioural economics POV – check out this prior post). In other words, we are terrible business administrators, since our decision-making process is affected by an ocean of biases, moods, gaps and feelings. To illustrate, some of the mental tricks – cognitive biases is a more exact term – that affect us are:

- Anchoring: we are amazingly susceptible to be affected by recent data, info and events, which anchor our analysis and deviate our conclusions and decisions of current events and decisions. For example, if I ask you for the distance between Chicago and NYC, is it more or less than 800 miles, you will probably go for a range of answers between a 1000 0r 600 miles. But if the question changes a little bit (is it more or less than, say, 30o miles) you will probably go for something around 500 or 600 miles. Another case: if, during breakfast, you throw the hot coffee mug and stain your blouse or shirt, a bad-day feeling is prompt to appear. Irrational? Yes! But true it is as well, that´s the human nature. Now let´s imagine a scenario when a board is approving budgets for launching a series of projects and the immediate prior event in agenda was to grant a prize or recognition for a successful project. You see my point? All the budgeting exercise will be biased, anchored by the warm feeling of success derived from the prior point in agenda.

- Availability: this cognitive bias affects our appreciation of the frequency of an event, assessing it in terms of how many examples come handy to our mind. For example, if I ask what is more frequent: homicides or suicides, you will probably go for the first, since the media floods us with examples. Now in the org world, let´s imagine a scenario where executives are discussing where to put the money an AI vs a Cloud project. There are almost no examples in the company associated with the first, and the Cloud area has been succesful… in this scenario, the AI project is basically doomed in spite of an excellent business case and ROI – the execs will probably see the Cloud one a s a “safe plan” vs an uncertain bet.

- “Status quo” bias: this bias relates to our difficulty to alter the momentum, the current course of action, the current state of the situation – we have all heard that “profound” rationale “because that´s the way things are done here” or its close relative “because the boss says so” or similar… No need to provide lots of examples with this one.

- Herd mentality: It is amazing how much do the others opinions affect us! Retailers know this and the tag “bestseller” is a great sales tactic, stores know this and it works either online or in brick-and-mortar stores. Also, more than a single sad traffic accident has occurred when the first kid crosses the street (eg, bike gangs) and the other ones follow him/her without checking. This herd behaviour has its absolute “twin” in the moder organization in the way business cases, projects, programs, deliverables and changes are voted for approval. Many times, in a sign of respect, the first vote is granted to the “hippo” (“highest paid person in the organization”) and from that point on the faith is sealed, but regardless being the “boss” the first one voting, the prior votes will bias the rest. Evidently, this is a terrible methodology for decison taking and a true assault on organizational governance.

Add to the aforementioned portray of our human biased nature the absence of process frameworks such as PRINCE 2 (check out the exact data in the PMI Pulse of the Profession 2018 report) and we got a recipe for disaster. Under the light of all the contents of this post and the prior ones, we MUST do something to improve the way that organizations design and steer their governance, in order to improve the sad ratios of failed projects. If you have been following this series of posts, I guess you already have your own ideas in mind. I will share my own in the next post: this one is already a long one and we need your undivided attention for what´s coming next.

I would love to hear your comments: don´t be shy. See you soon!

“Men are not prisoners of fate, but only prisoners of their own minds.” – Franklin D. Roosevelt

Bonus material:

Reflexiones de un PM en un mal día (parte II) / The deliberations of a PM on a bad day (part II)

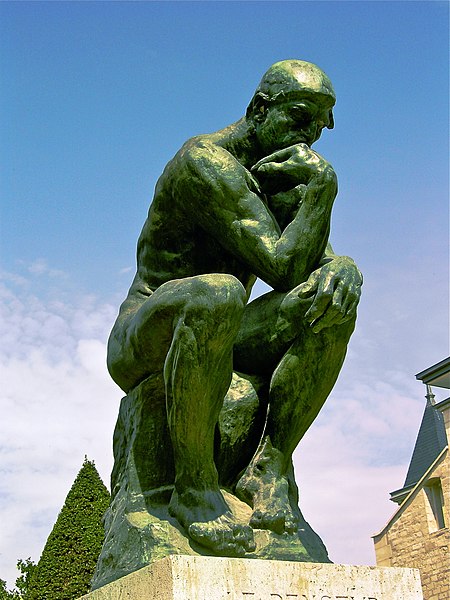

El Pensador / The Thinker – A. Rodin (photo by Andrew Home)

VERSION EN ESPAÑOL (ENGLISH VERSION BELOW)

“La ignorancia es la semilla de todo mal” – Platón

En un artículo/post anterior (adivinen su nombre…) dijimos que la causa última – lo que en inglés se llama la “root cause” – asociado al fallo de tantos proyectos (en mi humilde opinión, de la mayoría) es la organización: la empresa o entidad como tal. Más aún, dijimos que eran los procesos organizacionales los culpables: procesos mal diseñados, mal implementados o mal ejecutados (o una combinación de estos aspectos). Tenemos entonces a un sospechoso: el sistema como tal, y caracterizamos a este sospechoso bajo el calificativo de una deficiente o incluso ausente gobierno corporativo: se trata de ORGANIZATIONAL GOVERNANCE. Postulo entonces que el fallo de la mayoría de los proyectos no se debe a causas nacidas dentro del proyecto, sino a aspectos coyunturales asociados al entorno del mismo. Antes de brindar algunas ideas para atacar este “enemigo universal”, permítaseme justificar por qué sostengo que es ese el meollo del problema. Quiero decir, de momento es solo mi opinión: no he argumentado ni he brindado evidencia que sostenga la hipótesis. Procedamos entonces a aportar una justificación.

Comienzo con datos. Vamos entonces al ultimo informe “Pulse of the Profession”, edición 2018, por el Project Management Institute (PMI). Es en la página 25 de este informe (parte del Anexo), se pregunta (la traducción es mía): “De los proyectos iniciados en su organización en los últimos 12 meses que fueron juzgados como fallidos, cuáles fueron las causas primordiales? (Seleccione hasta 3).” Luego se provee el compilado de las respuestas, que incluye 17 causales. Me permito transcribir aquí el top 7:

- Cambio en las prioridades de la organización: 39%

- Cambio en los objetivos del proyecto: 37%

- Recopilación incorrecta de los requerimientos: 35%

- Visión o meta inadecuada para el proyecto: 29%

- Comunicación pobre o inadecuada: 29%

- Oportunidades o riesgos no fueron definidos: 29%

- Inadecuada gestión del cambio: 28%

Propongámonos la meta de tratar de encontrar un mínimo común denominador en esta lista. Es retador puesto que a primera vista, estas razones para el fallo en los proyectos aparentan ser algo disconexas. Sin embargo, si miramos más atentamente, podemos ver que la palabra “cambio” se menciona en tres de ellos. En otros tres de ellos se habla de una meta inadecuada y de requerimientos incorrectos (una visión inconexa con la estrategia organizacional o bien ajena a las necesidades), además se menciona una mala gestión del riesgo (nótese que el mismo PMI utiliza el término “riesgo” de una manera cuestionable, puesto que en este informa lo utiliza como sinónimo de “Amenaza” y no como sinónimo de evento incierto; véase la definición de “Risk” transcrita abajo). Los otros dos factores mencionan aspectos de comunicación y costos. Sostengo que el mínimo común denominador (o al menos, la mejor aproximación que puede haber a una causa común) es un asunto ajeno al proyecto: no es una “infección local”, se trata más bien de un “mal pandémico” asociado más bien a la ORGANIZACIÓN.

Prosigo: las tres razones que expone Mr. Mark A. Langley (Presidente & CEO del PMI) para justificar el hecho de que el 10% del presupuesto global en proyectos se “vaya a la basura” debido a un desempeño inadecuado son (PMI´s “Pulse of the Profession” report 2018, página 2):

- Las organizaciones fallan a la hora de intentar cerrar el “gap” entre el diseño de la estrategia y su ejecución/delivery.

- Los ejecutivos no reconocen que la estrategia se implementa a través de los proyectos.

- La importancia fundamental de la disciplina del Project Management como el “driver” de la estrategia organizacional no es adecuadamente interiorizada.

Lo interesante es que el PMI (ciertamente no en ese informe y – que sea de mi conocimiento – en ninguna otra parte) se pregunta el POR QUÉ se presentan esos problemas. De nuevo, postulo aquí que se trata de un asunto de (deficiente) gobernanza: en una analogía, cual si fuera una persona que desea bajar de peso y no puede imponer su voluntad para mantenerse a dieta, la organización carece del “auto-dominio” para comer nutritiva y sanamente – léase que le falta la capacidad de imponer la estrategias que define (ya hablaremos de las razones). Siguiendo la analogía, la organización tampoco acepta que los proyectos adecuados son esos platillos nutritivos y correctos que la llevarán al peso deseado y desconoce el valor del ejercicio y la nutrición (el Project Management).

Me voy a permitir seguir argumentando: el mismo reporte 2018 indica que solo el 37% de las non-enterprise-wide PMOs están altamente alineadas con la estrategia organizacional. Es decir, el 63% no lo están. En el caso de las enterprise-wide PMOs (EPMOs) el resultado no es mucho mejor: solo el 41% lo está. A mi parecer, esto es grave: si bajando un solo nivel de management (C-Suite a Enterprise PMO) se perdió el alineamiento en el 60% de los casos… ¿qué podemos esperar a la hora de bajar al nivel de los proyectos, por no hablar de sus requerimientos y entregables? Además, la disciplina del Portfolio Management es gestionada solo por el 48% de las EPMOs, y marcos normativos como PRINCE2 es usado solo por el 2% (!) de las organizaciones. Los resultados de la pregunta asociada a la madurez organizacional en torno a proyectos, programas y portafolios tampoco son alentadores. Otro resultado altamente contrastante es la respuesta a la pregunta “”Qué tan exitosa calificaría a su organización desarrollando lsa siguientes actividades sobre los siguientes tres años – formulación de una estrategia adecuada para las condiciones cambiantes del mercado?” Los ejecutivos calificaron como “Excelente” en el 43% de los casos y “Bueno” en un 50%, mientras que los líderes de PMOs indicaron un 13% yu un 46% en esas categorías de respuesta… Hmmm… me pregunto cuáles serían las respuestas en el caso de preguntarle esto a los Program y Project Managers. La distribución de respuestas también contrasta a la hora de preguntar por la priorización de los proyectos: aparentemente los Ejecutivos creen estar haciendo un excelente trabajo… pero el resto de la organización no coincide con esta apreciación. Tengo algún otros puntos, pero para efectos de mantener este artículo de un tamaño “digerible”, voy a dejar mi argumentación hasta aquí: el “fiscal” descansa.

Sostengo entonces que esta pandemia está asociada a problemas de carácter estratégico, como lo son la visión, misión y objetivos organizacionales, y el alineamiento de los portafolios, programas y proyectos con los mismos. Finalmente, sostengo que este problema de alineamiento se deriva a su vez de un modelo de gestión de la gobernanza obsoleto, que como la teoría económica de hace solo unos 30-40 años, se erige sobre una serie de supuestos erróneos que desconocen la curiosa naturaleza del ser humano.

En el siguiente artículo de esta serie, vamos a explorar cuáles son esos supuestos que corrompen la toma de decisiones y ahondaremos en los problemas del modelo “usual” de gobernanza en las organizaciones, modelo que está “diseñado para fallar” y termina haciéndolo “brillantemente” de mil y una formas: aprobando el lanzamiento de proyectos que no deberían aprobarse, sobrecargando el “pipeline” con más trabajo de lo que los equipos organizacionales pueden gestionar, apurando de manera desmedida esfuerzos, etc. etc.

¿Curioso? Eso espero – le espero en el siguiente post…

Material complementario / fuentes:

- Informe “Pulse of the Profession 2018” por el PMI, haz click aquí

- Definición de riesgo del PMI: “El riesgo de un proyecto es un evento o condición incierta que, de producirse tiene un efecto positivo o negativo en uno o más objetivos del proyecto, tales como el alcance, el cronograma, el costo y la calidad”

- “El pensador”, la estatua mostrada al principio, haz click aquí

ENGLISH VERSION

“Ignorance, the root and stem of all evil” – Plato

In the prior article of this series (guess that post´s title…) we said that the root cause behind the failure of so many projects (in my humble opinion, of the majority) is the organization itself: the company or entity. Moreover, we said that the organizational processes are the ones to be blamed: processes that are faulty designed, faulty implemented, or faulty operated (or a mix of those faults). We got as such a suspect: the org system, and we characterized the suspect under the ORGANIZATIONAL GOVERNANCE tag. As such, I state that the failure of the majority of the projects is a cause not hidden within the project itself, but in the environment around it. Before I suggest some ideas in order to tackle this “universal enemy” of Project Management, let me justify why I state that this is the real enemy. I mean, to this point, this is basically an opinion, but I have not provided arguments nor evidence to back it up: let´s proceed with those right away.

Data comes first… There is “gold” hidden in the last Project Management Institute (PMI) “Pulse of the Profession” report v. 2018. Let´s jump to page 25, where this question is raised: “Of the projects started in your organization in the past 12 months that were deemed failures, what were the primary causes of those failures? (Select up to 3).” Then the stock of answers is provided. Below the top 7:

- Change in organization’s priorities 39%

- Change in project objectives 37%

- Inaccurate requirements gathering 35%

- Inadequate vision or goal for the project 29%

- Inadequate/poor communication 29%

- Opportunities and risks were not defined 29%

- Poor change management 28%

Let´s try to figure a lowest common denominator to this list. It is a challenge because at first glance, the reasons seem to be rather arbitrary. But when we take a closer look, we notice that the word “Change” is mentioned in three of those. Another two mention an inadequate goal and inaccurate requirements (in other words, a project vision not aligned to the organizational strategy or goals – changes and changes are required to adapt along the way). Failed risk management is also there (notice that the PMI itself is doing a corrupt use of the term risk in this report, since it it uses it as a synonym of threat instead of the official definition associated to uncertainty – see official definition below). The other factor is linked to communication. I assert that the lowest common denominator (or its best approximation, if you will) is associated to the organization: its a pandemic fault, not a “local disease”.

Let me continute: the three reasons that Mr. Mark A. Langley (Presidente & CEO, PMI) mentions as the rationale behind the fact that 10% of the global project budget is literally wasted are (PMI´s “Pulse of the Profession” report 2018, page 2):

- Organizations fail to bridge the gap between strategy design and delivery.

- Executives don’t recognize that strategy is delivered through projects.

- The essential importance of project management as the driver of an organization’s strategy isn’t fully realized

The interesting thing here is that the PMI (certainly not in this report and to my current knowledge, nowhere else) ever asks WHY do these things happen. Again, I avow that this happens due to deficient organizational GOVERNANCE: in an analogy, like a person that wants to cut weight but cannot stick to the diet, the organization lacks the “self-control” to eat in a healthy and nutritive way (it lacks the ability to implement the defined strategy and select the right projects, we will talk as of the why soon). Continuing with the analogy, the organization also neglects the importance of those nutritive meals and of exercise which are the driver to the right weight (meaning, the importance of enforcing healthy Project Management).

And I have even more reasons to support my point: according to the same Pulse of the Profession report v.2018, just 37% of non-enterprise-wide PMOs are highly aligned to the org stratetgy. In other words, 63% are not. In the case of enterprise-wide PMOs (EPMOs) the result is frankly not much better: only 41% are. To my understanding, this is a big issue: if going down just one step of the org ladder (C-Suite to an EPMO level) generates strategical misalignment in 60% of the cases, what can we expect when we go down to the project, requisites and deliverables level? To make things worse, the same report states that Portfolio Management is steered just by 48% of the EPMOs and that powerful normative and structuring frameworks such as PRINCE2 is used just by 2% (wow!) of the organizations. The results that measure maturity level aren´t also heartening.

Yet another enlightening point is the answer to the question “How would you rate your organization’s success in performing the following activities over the last three years? – Formulating strategy appropriate for changing market conditions?” Execs went for “Excellent” in 43% of the times and “Good” in a 50%, whereas PMO-leads stated 13% and 46% for those categories (Excellent and Good) Hmmm… I wonder which would be the percentages if those questions were raised to PgMgrs and PMs. The contrast between Execs and PMO-leads perception is also apparent when asking about the quality of the project prioritization efforts: it seems Execs are quite positive about their work but the rest of the org is not very fond of it. I have even more arguments and evidence to support my case against organizational governance, but for the sake of brevity, I´ll leave it here: the prosecutor rests.

CONCLUSION: I affirm that the core cause is associated to strategic issues and its steering through the org: misalignment of the portfolios, programs and projects to the org strategy. And I finally assert that these alignment problems are due to an outdated governance model across our organizations that, like the economic theory that ruled just about 30 or 40 years ago, relies on a series of faulty assumptions associated to the way we human beings live, take decisions, enact and act.

In the next post of this series we will examine which are those assumptions and biases that corrupt the strategic and decision-making processes and we will deep-dive in the problems associated to the “standard” organizational governance model, which is “designed to fail”: and indeed it fails brilliantly, overloading the pipelines, approving for launch or for next-phase a load of “mutant” endeavors, smashing timelines, etc. etc. And we will also suggest some ways to tackle the problem – or at least reduce its intensity.

Curious? I hope so: see you in the next post of this series…

BONUS MATERIAL:

Reflexiones de un PM en un mal día (parte I) / The deliberations of a PM on a bad day (part I)

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL (ENGLISH VERSION BELOW)

“Los cántaros, cuanto más vacíos, más ruido hacen.” – Alfonso X el Sabio

Serrat canta “Hoy puede ser un gran día”… pero ciertamente hay días que no son así. Como Gerente de Proyectos (Project Manager – PM) estos días aciagos se presentan más seguido de lo que quisiéramos. Recuerdo uno de esos días sucedido recientemente. Con la cabeza fría, puedo identificar (al menos) los siguientes factores como parte de la receta del desastre:

- Un Portfolio Manager con una visión sesgada de los proyectos y programas bajo su cargo: diríamos que el caballero en cuestión vivía su puesto mirando siempre “hacia arriba”, hacia la Alta Dirección y el “C-Suite”, y nunca hacia el portafolio, salvo para dar direcciones.

- Un Program Manager del área en que me desempeñaba (a la cual reportaba directamente) con un estilo gerencial absurdo. Su mantra era “quédese en su caja”: una manera muy directa y poco poética de enarbolar la bandera de los “silos” o “compartimentos estancos” organizacionales. Además de ello, una limitada capacidad de escucha. y el sistema de escalación era disfuncional.

- Ausencia de un Project Charter o SOW confiable: me encontraba luchando en el proyecto desde hacía casi 6 meses y aún no existía un documento que oficializara su alcance, objetivos, presupuesto y otros “detalles”.

- Ambiente generalizado de premura y urgencia: deadline inamovible y, por decir lo menos, poco realista. Todo es “para ayer”.

- Alcance (scope) “saltarín”: la cantidad de elementos a desarollar en el proyecto cambiaba a un ritmo insólito, inclusive semana a semana – el término “scope creep” se quedaba muy corto.

- Juego de la “papa caliente” con la responsabilidad: más que un esfuerzo conjunto entre los diferentes equipos desarrollando los diferentes proyectos y programas del portafolio para entregar a tiempo la masiva cantidad de productos (entregables), el tema recurrente en el día a día era un juego político en donde lo más importante era que la culpa no recayera “en mí”: un juego de búsqueda de culpables y evasión de responsabilidades, amén de falta recurrente de coordinación y por supuesto de visión y trabajo en equipo.

- Mal ambiente laboral, epidemia del síndrome de “burnout”, faltante crónico de staff, alta rotación, etc.

Coincidará conmigo en que esta es la “tormenta perfecta”: una acumulación de factores que solo puede devenir en un proyecto / programa / portafolio fallido – independientemente del presupuesto, el cual, como adivinarán, era limitado y controlado con “marca personal”. Con el paso del tiempo, reflexioné: ¿Existirá un factor común que es el verdadero causante de todos estos (en algunos casos aparentemente inconexos) problemas? ¿Hay una causa raíz “maestra” subyacente a todo este desastre, un mínimo común denominador? Y, para rematar: ¿Es esto culpa del PM o de alguien más, y quién es ese “alguien más”? Unas cuantas lecturas, incluyendo breves repasos del PMBOK, el “Rita”, PMI´s “Pulse of the Profession”, algunas conferencias y artículos varios de estrategia y gerencia pero sobre todo un análisis concienzudo me llevaron a una conclusión general: efectivamente, hay una causa raíz detrás de todo esto: la organización como tal. Puede sonar en primera instancia como una perogullada, pero analicemóslo un momento: el problema no es el PM, tampoco el PgM y tampoco el PfM. Así que no hay que “echarse encima el muerto” en la conciencia. El problema es el SISTEMA: cuando en una organización la norma es el desorden, la sobrecarga laboral, la corrupción de prioridades, sobrecarga del pipeline de proyectos, etc. etc. entonces no es alguien, son los procesos globales de la organización los que están mal diseñados, mal implementados o mal ejecutados (o estos tres problemas a un tiempo). Y esto a su vez puede traducirse en una palabra: mala (o ausente) gobernanza: léase gobierno corporativo, pasando por elementos tácticos y cuasi-operativos.

Tenemos entonces un diagnóstico: un sospechoso, el supuesto “villano de la película”. Pero… ¿Cómo podemos estar seguros de que este es ciertamente el culpable y qué hacer ante esta triste realidad? Ánimo, hay esperanza: dejaremos esas reflexiones para las siguientes partes de este análisis, nos vemos en los próximos posts…

“Un hombre con una idea nueva es un loco hasta que la idea triunfa.” – Mark Twain

ENGLISH VERSION

“The empty vessel makes the loudest sound.” – William Shakespeare

Cat Stevens sings “Morning Has Broken” in an all-positive mood, but sometimes… oh gosh it isn´t a good day. As PMs, those bad times come more often than what we would linger for. I remember one of those days. With a cushion of months in between and a fresh and more objective perspective, now I can identify (at least) the following list of factors behind the “Perfect Storm” scenario hailing over that particular project:

- A Portfolio Manager with a biased, unbalanced perspective of the programs and projects under his accountability: this person was leading with the eyes always pointing at the Executives, Sponsors and the C-Suite, with virtually no time nor attention for the team under his command.

- A Program Manager directing the area in which I was working (I reported directly to that person) with an absurd management style: that person´s Project Management mantra, preached to all the team, was “stay-in-your-box” – do not ask about other areas and projects, do not request info on the general effort status, shut up and look down. Of course, this translates into the official empowerment of organizational silos, not to mention a very limited capacity to listen.

- No Project Charter or SOW available: we were six months already into the effort, and there was no official charter nor Statement of Work… requisites were managed in a pretty muchinformal way and in any case, there was no definitive document stating the project objectives, terms and conditions.

- An universal environment of urgency: if anyone received a task or an instruction, the rationale was always urgency, “it is late”.

- Project and Program scope capable of competing in the “Calaveras County Jumping Frog Jubilee” (remember Mark Twain´s short story? Check the link below): the scope changed week by week. The list of applications in our scope mutated sometimes even twice per week.

- Responsibility was managed like the a hot potato game: as such, the spirit was not to work as a team and actually solve issues, but to toss the blame on someone else, fast, before it hurts you. As such, the Project Team behaved in a political and evasive way, creating lack of trust and unnecessary antagonisms.

- Staff issues: we were always short on staff, people were demotivated and “burned-out”, the project suffered due to high staff turnover and attrition.

Of course, the sum of these factors create a nearly impossible scenario, regardless the budget allocated for the effort (which, of course, was limited and strictly controlled). This set of conditions steer the project / program / portfolio towards failure. As stated above, with the perspective of time and distance, I have meditated: is there a common factor, a root-cause, a minimum common denominator behind all the above listed issues? Moreover, if that is the case, what is that “sum of all fears” thing, and is the PM to be blamed? A series of lectures, including the new PMBOK v6, Rita Mulcahy´s famous training book, PMI´s latest “Pulse of the Profession” report, a couple conferences and other technical articles but mainly a lot of internal deliberation have led me to a sound conclusion: YES, there is a common cause, and it is the organization itself, the company. This may sound initially as a “duh” statement, but before you bully me, let me present the nuts and bolts to extract the real value out of it. First of all, we need to be clear that the PM (nor anyone in the project, nor the PgM of the PfM or even the Sponsor) is to be ultimately blamed. This is not a small thing: so first and foremost, don´t feel personal frustration or take the blame. The root cause lies in the SYSTEM behind the projects: its not the actors, its not the play, its the stage and the theatrical company (Shakespeare would be proud of the analogy I guess). When disorder, lack of priorities, lack of staff, work overload, high attrition, pipeline “cholesterol” and overload are the norm, then something is utterly wrong at a general level. This means that the blame is not to be put on someone – and especially not you as the PM (perhaps C-Suite, but let´s avoid the blaming exercise for the time being) but on the organizational PROCESSES, which may be faulty designed, faulty implemented or faulty executed (or a combination of those). In a nutshell, all this mess can be translated into a single evil: tainted, degraded organizational GOVERNANCE.

So, we have come to a conclusion and we now have a SUSPECT. Still, how can we be sure that this is indeed the despicable villain behind all this mess and how to tackle this inconvenient reality? We will deal with these questions in the coming posts. Stay tuned…

“A person with a new idea is a crank until the idea succeeds.” – Mark Twain

Bonus material:

- Mark Twain´s short story – “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County“

- PMI´s “Pulse of the Profession” report 2017: click here

- PMI´s “Pulse of the Profession” report 2018: click here

- Alfonso X of Castile: click here – he is the author of the top quote in the Spanish version of the article: “Pitchers, the emptier they are, the louder they sound”